Science Play of the Day: The Earthworks

The Earthworks by Tom Morton Smith takes place in a hotel in Geneva on the eve of the switch on of the Large Hadron Collider.

‘Two strangers – a journalist and a scientist – share their experience of loss and hope in a funny but deeply touching one-act play.’ -Playtext published by Oberon Books.

First performed at the RSC Mischief Festival at Stratford-upon-Avon in May 2017.

You’re one of those ‘because the sun’s going to expand and swallow the earth in four billion years…everything is therefore meaningless’ kind of people. Leave the Ladybird Book of Nihilism on the shelf and tell me something real.

Clare to Fritojof, The Earthworks, Scene 5

Michael Frayn Speaking to Kate Mosse at Chichester Festival Theatre

Certain to Please? – The Uncertainty Principle in Theatre 2017

‘The Uncertainty Principle’ is the subtitle of Simon Stephens’ new play Heisenberg, currently running at Wyndham’s Theatre in London. But this is not the only time the principle has been explored on stage during 2017…

Much like Simon Stephens’ other new play this year, Nuclear War, the title of Heisenberg: The Uncertainty Principle is not particularly indicative of the content. Heisenberg is a touching romantic comedy in which the uncertainty principle makes only the loosest of appearances. This presents no difficulty in itself – artists are of course entirely entitled to use whatever ideas they choose as a title for their work. However, perhaps it indicates something about the cultural climate in 2017 that producers can confidently borrow an otherwise esoteric scientific concept to market a main stream West End production.

The Royal Court Theatre, which produced Stephens’ Nuclear War, also premiered Lucy Kirkwood’s new work The Children earlier in the year. This was a dark and reflective piece about the legacy of three retired nuclear scientists of the baby boomer generation. As thoughtful as The Children was, it was surely Lucy Kirkwood’s other major new work Mosquitoes at the National Theatre that was arguably the piece of standout science theatre in 2017.

Mosquitoes is set at the time of the switch-on of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in 2008. A play that includes a character called ‘The Boson’ immediately rings alarm bells over the risk of didactic dialogue and some superficially inserted science. Far from it, Mosquitoes delivered an absorbing and funny family drama with complex three-dimensional characters that we come to care deeply about. The scientific setting sits very comfortably within the play, complementing but not dominating the narrative. It is the tale of two sisters, Alice – a staff scientist at CERN (played by Olivia Williams) – and Jenny, her troubled and arguably naïve sister (Olivia Colman). Contrary to Alice’s high minded approach, Jenny has developed her own brand of tabloid-style scepticism and fact-free opinion that results in difficult consequences for her and her family. As a politician famously once said, ‘people in this country have had enough of experts’.

Mosquitoes also features two relatable teenage characters who are grappling with their sense of place – both literal place (displaced from England to Geneva) and virtual (negotiating the brave new Snapchat world). What Kirkwood and director Rufus Norris achieved with Mosquitoes is the rare combination of a full length two-act play that draws heavily on science and yet comfortably stands alone as an enjoyable, relevant and probing piece of theatre.

It is the character of the sisters’ mother Karen (Amanda Boxer), a retired Cambridge scientist herself, who brings up the uncertainty principle in the form a joke told to her daughter (partially to alienate Colman’s less science-savvy character). The principle (and the joke) is never overtly explained for the benefit of the audience. If we are also to feel alienated rather than enlightened is something that we are left to decide for ourselves, much to the credit of the writer.

Mosquitoes was not the only new play this year set around the opening of the LHC. The Royal Shakespeare company took this on as part of their Mischief Festival in the spring when Tom Morton-Smith (Oppenheimer 2015) delivered a one-act piece for ‘The Other Place’ studio theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. The Earthworks charts an encounter between a science journalist and a postdoc researcher, also on the eve of the LHC switch-on. It’s a very neat little piece (on a similarly human scale to some of Nick Payne’s one act plays) with some fun science inserted (at one point non-Newtonian fluids are demonstrated live on stage with custard borrowed from the kitchen of an up-market hotel). The Earthworks offers a valuable new perspective that other ‘science plays’ have not yet really approached – a sense of the potential conflict between the need for click-friendly news nuggets to sustain modern online media and the more considered, often-long term nature of scientific research. There was plenty of great material to work with here and The Earthworks adds a great deal to the genre. However, towards the end of the play, real science is conflated with (albeit plausible) science fiction. This worked well to advance the narrative in a moving way, but it felt slightly disappointing to mix fact and (near) fiction in the same piece given that there is already so much great real science in the play.

The confusion of fact and fiction is central to Terry Johnson’s 1982 play Insignificance, currently enjoying a revival at The Arcola Theatre in Dalston. The Professor, The Actress, The Senator and The Ball Player all meet in a fantasy encounter in a 1950s Manhattan hotel room. The contrivance works because the characters (although never named) are of course Albert Einstein, Marilyn Monroe, Joe McCarthy and Jo DiMaggio. It’s a fun and at times sinister piece with some great casting by director David Mercatali. The gentle Einstein (Simon Rouse), a flighty but vulnerable Monroe (Alice Bailey Johnson) and an oafish DiMaggio (Oliver Hembrough) spar and with each other and with the ruthless Senator McCarthy (Tom Mannio). Since Einstein is in nearly every scene it comes as no surprise that science makes an appearance. However it is in fact Monroe who gives a breathless and accurate summary of the principles of special relativity to The Professor in the first act, before the play goes on to explore some its darker themes.

Shortly before the end of Insignificance Einstein makes a passing reference to the uncertainty principle. It drew a muffled but knowing response from members of the audience, who were perhaps conscious that this is not the only ticket in town with a bit of exposure to this particular piece of science.

It was of course nearly 20 years ago that Michael Frayn so successfully wove the uncertainty principle seamlessly into the structure of Copenhagen at the National Theatre. It seems almost churlish to note here that none of the recent productions discussed above manage to replicate that sophistication. However, the prevalence of the uncertainty principle in 2017 demonstrates that audiences are increasingly comfortable to engage with science in a theatrical setting. And that seems to be one principle worth pursuing.

Insignificance runs at the Arcola Theatre until 18th November 2017

Heisenberg: The Uncertainty Principle is at Wyndham’s Theatre until 6th January 2018

Interview: Director Matthew Xia on Blue/Orange at the Young Vic

The semantics of an argument between a senior and junior doctor form the basis of Blue/Orange, Joe Penhall’s play about a young black man who has been confined in a psychiatric ward. Matthew Xia directs a revival of Blue/Orange at the Young Vic Theatre between 12th May and 2 nd July, with Daniel Kaluuya, David Haig and Luke Norris in the cast.

nd July, with Daniel Kaluuya, David Haig and Luke Norris in the cast.

Science Centre Stage spoke to Matthew Xia about the process of staging this revival in the current climate of change in the NHS, about using words to create illusion and misdirection and the current place of medicine in theatre.

Can you give a little background to Blue/Orange and what it is about?

Blue/Orange was written towards the end of the late nineties by Joe Penhall in what was at the time his most successful play. It won the Olivier Award for Best New Play in 2000. The original production at the National Theatre starred Bill Nighy, Andrew Lincoln and Chiwetel Ejiofor. Sixteen years later we want to explore the same themes which feel ever more pertinent. There’s certainly a series of crises concerning junior doctors and beds and resources and all the things that have constantly plagued the NHS.

We start on Day 27 of a Section for a young black man called Christopher. He’s in for assessment and treatment over a course of 28 days. He’s on the 27th day, so he’s being released tomorrow. But the junior doctor, who is white, (Christopher is black) thinks that there is something in the diagnosis that is inaccurate and would like to have him stay for up to six months. In order to do that he needs the agreement of his senior consultant called Robert Smith. Ultimately the play is looking at the potentially subjective nature of diagnosis, particularly in psychiatry, and how that is affected by things such as unconscious bias, ethnocentricity, cultural specificity, and how these things cause us as humans to make subjective diagnoses, even with our best will and best intent in mind.

What the play really tries to tackle and what I’m personally interested in, is first, the kind of diametric argument that is presented. Joe Penhall’s great at writing complex, nuanced, detailed arguments. Secondly, you’ve got these two white doctors and their black patient so I guess the other thing that it really explores is the power structures inherent in patient-doctor dynamics and how that might have a bearing on diagnosis. It also explores the power structures within the relationship between a senior and a junior doctor and the expectations upon both of them in those roles.

Did you consult with doctors and psychiatrists during the development process to help understand the system they operate in?

Yes, certainly. My process anyway is to completely immerse myself in the world that the characters live in. The mental health guidelines from 1997, government documents, white papers, testimonials and a brilliant book called Users and Abusers of Psychiatry were really useful in the rehearsal room. The next stage was that the designer (Jeremy Herbert) and myself went along to the Maudsley Hospital. The play isn’t set in the Maudsley but it’s the crown jewel of mental health facilities. I went down there and spoke to occupational therapists who gave us a tour of the building so we started to get an idea of the environment that these people would be working in.

We met a brilliant man called Dr. Neil Brenner who is a consultant psychiatrist and had the most incredible array of stories and experiences. We’d read him small bits of the play and he’d respond to them, which gave us a sense of the truth of the world that we were trying to replicate and also some guidance on how far we could stray from the truth with the production.

How do you challenge without offending, upsetting or crossing the status boundary?

At at the turn of this century there was a very clear hierarchy [in medicine]. The junior doctor in this play is ideological and principled and that leads him to challenge his senior quite a lot. Dr. Neil Brenner says he would be out on his ear, immediately. It was useful because it actually meant we could temper some of those challenges. Then there is a much more interesting game to navigate. How do you challenge without offending, upsetting or crossing the status boundary? I think this makes for a much more interesting reading than a hot headed, fiery, junior doctor who doesn’t quite know his position.

Given that you were told Joe Penhall was something of a soothsayer for predicting future changes in the NHS back in 2000, do you think the play says anything about future patterns and how things might develop from here? Or is it more of a snapshot of where things are?

I think it’s more of a snapshot of where things are but I think that brilliant thing of putting a play on at a different time to when it was written means that it becomes a prism that refracts today’s thinking and understanding. You spot new patterns and different correlations that maybe weren’t so readily apparent the first time round. I think we live in a very different, much darker world than we did in 2000, a kind of post 9/11 world. Christopher thinks his father might be Idi Amin at one point – that’s ambiguous, and it’s meant to be ambiguous. Is his father Idi Amin or not? But he says at one point he’s a Muslim fundamentalist. Now in 2000 that would have rung out in such a different way to how it rings out now. This man being attracted to this hugely powerful Muslim extremist- it says something very different. So I guess my point is that the play has stayed the same. We have changed and it will be interesting to see how that relationship between audience and piece has changed because of the shift in society.

Does your interest and background in illusion have any bearing on your work in theatre?

I think they are quite separate interests for me. My interest in illusion is an interest in amazing people and in small theatrical events and happenings. In my last show (Into the Woods) it was much easier to employ magic and trickery in a fairytale land. I think where the magic actually comes into Blue/Orange is that it’s ultimately a play about semantics and the inherent power of words and the slipperiness of words. Of course that was all coming out of people like Alastair Campbell and the Blairites – that was the world that this play was written in. Spin was huge. Somebody of a particular class or esteemed in a particular fashion could say something that meant one thing and if somebody else said it – it meant something completely different. It was a game of rhetoric. I think that’s the sort of magic that I’ve become interested in in the last ten years – the misdirection of words and the use of words to mask and create smoke and mirrors. That is almost certainly within the play. The character that David Haig plays is so manipulative and controlling and Machiavellian in the way that he uses his words. He’s incredibly calculating, incredibly deft with his deployment of words. I’ve always had that interest in magic and it’s something that’s come to the forefront more recently with psychological illusionists.

Given that you have quite a small cast, how does your rehearsal process work – do you like to work with the writer in the room?

I spent a lot of time with Joe in the casting of the show and very early on in rehearsal. He came in and pointed out where the pitfalls were to be found or the problematic spots or certain things that we just have to get right with this play otherwise is just doesn’t quite work in the way that it’s meant to. It’s incredibly useful, incredibly helpful. But I think as with all plays ultimately, even if it’s a new play, at some point the writer needs to leave having known that they’ve done their job, which is to write the play and to pass that over to a team who would then bring it to life. One of the problems with having a writer in the room too long is that everybody looks for direct answers. So as opposed to having an investigative exploratory process you just go ‘why do I say this?’ or ‘why does he do that?’ instead of working through your own system of logic as to why you get from one thought to the other. It’s been great having Joe so close to this production and equally it’s been great, as always, being left to our own devices to make a play.

I spent a lot of time with Joe in the casting of the show and very early on in rehearsal. He came in and pointed out where the pitfalls were to be found or the problematic spots or certain things that we just have to get right with this play otherwise is just doesn’t quite work in the way that it’s meant to. It’s incredibly useful, incredibly helpful. But I think as with all plays ultimately, even if it’s a new play, at some point the writer needs to leave having known that they’ve done their job, which is to write the play and to pass that over to a team who would then bring it to life. One of the problems with having a writer in the room too long is that everybody looks for direct answers. So as opposed to having an investigative exploratory process you just go ‘why do I say this?’ or ‘why does he do that?’ instead of working through your own system of logic as to why you get from one thought to the other. It’s been great having Joe so close to this production and equally it’s been great, as always, being left to our own devices to make a play.

Similarly with designers, do you bring your own ideas beforehand and work through it with them in rehearsal or do you leave it to them to approach you with ideas?

The reason that I make theatre and one of the reasons that I enjoy making theatre, is the collaborative nature of the arts. It’s very much me and Jeremy Herbert sat in a room reading the play very badly to each other and then finding what it needs, what it’s about, what moments have to be realized in terms of a pragmatic approach to the work, versus a more abstract conceptual approach.

It’s ultimately a play about semantics and the inherent power of words

The idea that Christopher is in an institution, what does that mean? One of the decisions that we made is Christopher never leaves the playing area so that you know he is here constantly and it is his life that’s being discussed and that he is completely disempowered in those conversations. And of course time and place is the ultimate thing that you are hoping to communicate to an audience with your design.

That then develops into a series of images, references, sketches and drawings. I might walk past a painting or a piece of skirting board or a colour and just take a picture and send it to Jeremy. There’s quite a protracted process where we’re always reluctant to put anything down too quickly. Then you start playing in a 3D world with a model box. I always knew this was the presentation of an argument and what we’re looking at under the microscope isn’t actually Christopher. We’re not as an audience trying to diagnose Christopher. That might be part of the game that you play as an audience member but what you’re really doing is trying to understand how these doctors are arriving at these diagnoses or theories and the words that they use to bolster and strengthen that and the understanding that they might not necessarily be doing it for absolutely Hippocratic reasons.

Do you think there has been a recent shift towards an increasing representation of science and medicine on stage or have these subjects always been ripe for exploration in theatre and the arts?

I don’t personally feel like there’s been a shift. I think theatre can only ever respond to the here and now and particularly in the writing of new plays. Would somebody say that Alistair McDowall’s X at the Royal Court is an exploration of science when it’s set on a space station in Pluto? Ultimately it’s about the breakdown caused by isolation and loneliness. A play about science is still a play about human experience and I think these questions have always been asked whatever the current thinking of the time was. You could argue that The Alchemist by Ben Jonson is a play about the modern contemporary science and understanding of how elements may work. You could argue that Doctor Faustus with his investigations into magic and the occult is an exploration of science.

I think people are finding more interesting ways of putting stories about scientists and physicians and medical practitioners and engineers on stage. That’s possibly got something more to do with a slightly liberated way of approaching theatre that isn’t so bound by dialogue, dialogue, dialogue, next scene, dialogue. People are playing with projection and elements and smells and sounds. Is Peter Brooke’s The Valley of Astonishment, exploring synesthesia a play about science? Or is it a play about human experience?

Or are they one and the same?

Matthew Xia’s production of Blue/Orange by Joe Penhall runs at the Young Vic 12 May – 2 July. Tickets www.youngvic.org 0207 922 2922

Highlights from a Year of Science in Theatre 2015

In a year in which high-profile productions such as Photograph 51 and Oppenheimer attracted considerable attention for bringing science to the stage, 2015 was also a year in which smaller gems such as Islington Community Theatre’s Brainstorm shone.

It was arguably the star appeal of Nicole Kidman rather than the play that drew audiences to the Noel Coward Theatre in September to see Anna Zeigler’s Photograph 51. However, those who saw Kidman’s portrayal of Rosalind Franklin (for which she received an Evening Standard Theatre Award for Best Actress) in Michael Grandage’s production saw a theatrical depiction of an intriguing period in the history of science. Science Centre Stage spoke to Edward Bennett, who played Nobel prize wining biophysicist Francis Crick in the production, about his approach to playing a real-life character and visiting the archives at Kings College London. Photograph 51 is currently nominated for best new play in the What’s On Stage Awards (despite first being performed in the USA in 2007).

When Tom Morton-Smith’s play Oppenheimer opened at the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Swan Theatre at the beginning of the year, its subsequent success was sufficient to lead to a West End transfer. Commuters in London encountered hundreds of posters featuring John Heffernan as J. Robert Oppenheimer promoting the play at the Vaudeville Theatre where it played for two months. The Institute of Physics and Graham Farmelo arranged a panel discussion at the RSC in Stratford-upon-Avon in which the playwright, director Angus Jackson, physicist Prof. Frank Close, science journalist Alok Jha and former Times literary editor Erica Wagner discussed the themes of the play in an event chaired by deputy artistic director of the RSC Erica Whyman.

Another panel discussion in May at the Royal Society, also chaired by Erica Whyman, saw Tom Morton-Smith discuss Oppenheimer with Prof. Marcus du Sautoy, Prof. John Barrow and science-theatre scholar Prof. Kirsten Shepherd-Barr (whose new book Theatre and Evolution from Ibsen to Beckett was published by Columbia University Press in 2015).

Although Oppenheimer and Photograph 51 offered the highest profile portrayals of scientists in mainstream theatre last year, there were also some very strong smaller scale performances bringing together science and theatre, particularly generated by collaborations between scientists, theatre makers and writers.

An undoubted highlight of 2015 was Brainstorm, Islington Community Theatre’s uplifting and energetic piece exploration of the neuroscience of the teenage brain. It was performed by 10 teenagers with support from the Wellcome Trust and was devised by the cast with guidance from UCL neuroscientists Prof. Sarah-Jayne Blakemore and Katie Mills and directed by Ned Glasier. A hugely successful opening run at the small Park Theatre in January led to a well-deserved transfer to the National Theatre’s temporary theatre space in the summer. Islington Community Theatre then took part in Battersea Arts Centre’s Live From Television Centre project, resulting in a 30-minute version of Brainstorm becoming available on BBC iPlayer, substantially widening the audience it reached. Brainstorm will return to the National Theatre in 2016.

Another intriguing production benefiting from Wellcome Trust support in 2015 was Metta Theatres’ Mouthful, in which international playwrights were paired with scientists to produce six short plays about the global food crisis. The result was a thought provoking and engaging production at London’s Trafalgar Studios. Science Centre Stage spoke to Metta Theatre’s artistic director Poppy Burton-Morgan about the development process behind Mouthful and how the scientists and writers worked together to create the plays.

Menagerie Theatre also continued their strong programme of pairing academics and writers in their What’s Up Doc? series for the 2015 Hotbed Festival in Cambridge. Pictures of You was writer Craig Baxter’s latest collaboration with Dr. Martina Di Simplicio of the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit at Cambridge University, in which mental imagery was explored in a short play that was subsequently had a short run at London’s Soho Theatre.

There was barely space to swing Alan Turing’s bicycle in the upstairs space at the Arts Theatre (though they tried) as The Hope Theatre’s performed Snoo Wilson’s Lovesong of the Electric Bear in a quirky and offbeat take on the life of Alan Turing directed by Matthew Parker. Meanwhile, Turing also featured in That Is All You Need To Know at the New Diorama Theatre as Idle Motion performed their Bletchley Park inspired piece of remarkable devised physical theatre for the last ever time.

At the peripheries of the science-theatre genre lie certain plays presenting dystopic but feasible near-future scenarios. In 2015 the Royal Court Theatre’s production of Jennifer Haley’s The Nether asked pressing questions about the boundaries between the online world and reality during a 12 week run at the Duke of York’s Theatre. The Young Vic Theatre played host to Southampton Nuffield’s revival of Caryl Churchill’s A Number, exploring the possible consequences of where human cloning could take us. Science Centre Stage spoke to director Michael Longhurst about the background to the play and how he and Tom Scutt worked together on the striking set design.

The inestimable Tom Stoppard topped and tailed the year with his new neuroscience-inspired play The Hard Problem opening at the National Theatre in January and a revival of the little-performed Hapgood at Hampstead Theatre in December. Hapgood is a spy-thriller drawing on ideas from quantum physics which apparently baffled many who saw the original production in 1988. However, Stoppard has revised the play several times since, including an updated version for the Hampstead Theatre that runs until 23rd January 2016.

The Hard Problem will have its USA premiere from 6th January 2016 at he Wilma Theatre in Philadelphia. Stoppard discussed the play with philosopher David Chalmers, who first coined the term the ‘hard problem’ to address the question of consciousness, on stage recently ahead of the new production.

January 2015 saw the death of scientist and playwright Carl Djerassi at the age of 91. Djerassi’s writing about the relationship between science and theatre was extensive and he wrote many plays, including Insufficiency and Oxygen (with Roald Hoffmann) each constructed around some aspect of science. Despite at times being controversial, and with mixed reactions to his plays, his approach was spirited and there is no doubt Djerassi contributed a great deal to the consideration of the place of science on the stage. Jenny Rohn wrote thoughtfully about her own interactions with Djerrassi in a piece for LabLit in March.

If 2015 was a strong year for science in theatre then 2016 also has some interesting prospects in store. A new play by Nick Payne for the Donmar Warehouse opens in April. The Royal Shakespeare Company will apply their considerable resources and talents to a new version of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, arguably one of the early depictions of a scientist in theatre. But if Photograph 51, Oppenheimer and The Hard Problem were some of the mainstream successes of 2015, it is the smaller gems that may also be most worth seeking out in 2016.

Director Poppy Burton-Morgan Serves Up Science-Inspired Food for Thought

Collaborations between theatre makers and scientists can lead to work that tackles diverse and complex subjects. Mouthful is an interesting example. Developed by Metta Theatre and currently playing in an intimate space at Trafalgar Studios in London, the production comprises six short plays exploring different aspects of the global food crisis. Four actors play over 20 characters and the result in an absorbing, entertaining and surprisingly informative experience.

The writer of each play was paired with a scientist with expertise in a particular area of sustainable global food provision, enabled by funding from a Wellcome Trust arts award. The resulting series of plays includes visions of dystopian futures without food or water, mini domestic dramas and a brief musical performed by dancing insects…

Science Centre Stage spoke with the director of Mouthful, Poppy Burton-Morgan, about how Metta Theatre came to tackle the issue of global food sustainability on stage and how the playwrights and scientists worked together to create the six pieces.

What’s is the background to Mouthful, what’s it about and what are you aiming to achieve with it?

A few years ago in 2012 we commissioned six writers to write new short plays about the Arab Spring and wove the whole thing together into one play. Then in 2013 we were commissioned to develop a piece that was responding to political austerity – we used bread as a medium to explore that and how bread has been used in protest. Those are the conceptual seeds of doing something to explore the global food crisis through multiple voices. We’ve made quite a few pieces of what you might call science-theatre where we’ve collaborated with scientists in creating the work. So we took this one further in terms of commissioning six playwrights, each of whom were partnered up with a scientist, who all have different areas of research and specialisms relevant to the food crisis and food system and population ecology.

Some of the plays are incredibly dramatic. Some of them are little bit heart breaking

Each of them went off in their pairs and created these six stories that we’ve then woven together into one play. They take us all over the world. There’s some organic carrot farming in Columbia. There’s a play about the Tunisian bread riots back in 2010. There are two that are set in strange dystopian futures. There’s one where there are no more potatoes and one where we’ve almost run out of water. Each of them took a different foodstuff and explored something to do with that. Each one either has a foodstuff or drink physically on stage. They’re very funny, but as you can imagine some of them are incredibly dramatic. Some of them are little bit heart breaking. The great thing is that a few of them are laugh out loud comedy as well. It’s got a bit of everything!

It’s actually amazing the way technology has allowed us to create a truly international project

Did you give the writers and scientists a free hand to see what they came up with or did you help enable the process, for example with workshops?

Photo: Richard Davenport

The process was different for each partnership. Because it’s a completely international collaboration, the writers and the scientists between them cover four continents and a lot of countries. There was only one partnership where both the scientist and the writer were based in London. Actually for most of them it was about facilitating electronic introductions. Those relationships were really played out through email and Skype and occasionally phone calls and texts. We found in 2012 when we did the Arab Spring pieces (where we had international writers) that it’s actually amazing the way technology allows us to create a truly international project. We’re quite a small company, we don’t have the budget to fly everyone over, from Columbia, from America, from Finland. A lot of it has been done electronically.

There’s a real vogue for science-theatre that is exploring scientific ideas, scientific methodology

I’ve had quite a light touch in terms of the relationship between each partnership. For some of them I think it’s that the scientists would say ‘here is some research you could look into, here are some of my papers – does that provoke anything in terms of what you might write about, where you might go?’. And then I think for some of them it was a much involved, integrated process, and the writers sent them early drafts and some of the scientists would say – ‘actually, what you’ve written isn’t really possible or scientifically accurate and here are some papers that could take you in a different direction’. What’s really exciting is that some of them have really grappled with current research and current philosophical issues and ideas within science as well. But it feels like that bedrock has remained really accurate and at the heart of the plays.

Audiences want the thrill of theatre but they want the intellectual provocation of some really meaty ideas

Between each of the six stories there are info-graphic interludes of video projection where various facts pertaining to either to the story that you’ve just seen or the story that you’re about to see come up in an animated info-graphic way. Without becoming didactic and like a public lecture, you hopefully leave it feeling that you have learned something about the global food crisis and all of the science around that but in a way that doesn’t mean the plays themselves have to shoehorn in those facts. That feels really successful.

Did the writers deliver finished scripts or did the actors help devise some of it as well?

No it’s all very much script-based. So the writers and scientists worked together in developing each of the pieces. Things have evolved a little bit in rehearsals. We had a four-week rehearsal process. But nothing major in terms of re-writes. They all sit quite firmly within a conventional play, albeit a short play.

Is the global food crisis a particular topic you have had in mind to tackle for a while?

I think we felt really strongly that when we did these Arab Spring pieces in 2012 that the short play format is such a great way of examining a global system where there is a multiplicity of voices, opinions and conflicts between certain parties’ versions of events. The majority of the work we make is quite politically or socially engaged but also done in quite a theatrically imaginative way. We were really interested in how we could explore something as global and epic as the global food crisis through theatre and through a series of shorter plays, short stories, to allow us to show different voices and different sides of the argument.

We were really interested in how we could explore something as global and epic as the global food crisis

All of the six pieces (actually seven – there’s a secret seventh piece which is a four minute musical about entomophagy – a whole other thing!) are linked thematically. But they speak about such different aspects of the system, coming from such different perspectives, that I think it gives people an insight in depth to those six issues, but it also makes you step back and go ‘these are six tiny pieces of an enormous puzzle’. And the problem that we have to grapple with in the play and that we have to grapple with in reality is that that system is so inter-connected that you can’t solve it by saying ‘buy organic’ or ‘don’t eat meat’ or ‘do this’ or ‘do that’. There’s no one lovely catchall that would solve the system crisis. So hopefully the diversity of voices is a good way of demonstrating and exploring that.

Did the Wellcome Trust help facilitate the links with the scientists or is that something that you pursued directly yourself?

We went through that directly ourselves. Because we’ve done various science-theatre collaborations in the past we’re quite connected to the scientific community. The main scientific adviser is Professor Tim Benton who is the UK champion for global food security. Most of the other scientific collaborators were recommendations of colleagues or friends of his that he thought would be interested and provoked by the idea of an artistic collaboration. Which is lovely because they all have different areas of knowledge and they’re spread across the world – which feels like quite an exciting international thing.

The majority of the work we make is quite politically or socially engaged but also done in quite a theatrically imaginative way

Did adviser Prof Tim Benton come to the rehearsal room to advise?

We had several meetings with him early on before we’d even commissioned the writers in terms of how we would shape the project and the kind of scientists we would want to find to partner up with the writers and then he popped in and out of rehearsals. Once we had the scripts he read them all to check for accuracy and that theses are the right messages we want to be saying and are these the right provocations we want to be giving to audiences. We were really lucky in that one of our American scientists happened to be in the UK over the rehearsal period so she managed to pop by as well. For the others we filmed bits and used Skype so the cast could meet the international collaborators. We tried to keep it an open and welcoming project for everyone, even if they’re several thousand miles away that they still feel as involved as the writer who lives down the road and can just wander in.

Given the international scale and electronic collaboration it’s possible that some of the writers and scientific advisers may not even have actually met in person yet at all?

Absolutely. I think the majority of them haven’t. In some wonderful world where we transfer to the National Theatre or something and we have million of pounds (!) it would be such a wonderful thing to be able to fly everyone over and for everyone to meet in the flesh but everyone has to make to with virtual introductions at the moment. It would be lovely to tour the work to New York and show it to the American contingent of our collaborators, take it to Columbia, take it to Finland. So watch this space!

There’s no one lovely catchall that would solve the system crisis.

The success of Islington Youth Theatre’s Brainstorm (another science -inspired collaboration that transferred to the National Theatre) perhaps indicates a current taste for this type of work?

I think there’s an appetite for it. There’s a real vogue for science-theatre that is exploring scientific ideas, scientific methodology. People don’t want to come and see a public lecture. They want their theatre to still be theatrical. Hopefully what we do well is marry that integrity of scientific content with an imaginative theatricality and performance style. There are four actors who across the evening play 21 characters and all of them happen around the same dining table and stools so there’s a certain amount of imaginative leap that that the audience has to go on. Audiences want that, they want the thrill of theatre but they want the intellectual provocation of some really meaty ideas.

Poppy Burton-Morgan is Artistic Director of Metta Theatre. Mouthful is at Trafalgar Studios until 3rd October 2015

Actor Edward Bennett on Playing Francis Crick in Photograph 51

Fresh from an acclaimed season with the Royal Shakespeare Company, Edward Bennett is currently in the West End playing Francis Crick in Photograph 51 alongside Nicole Kidman. Edward told Science Centre Stage about his impressions of Crick, about visiting the historic labs at Kings College London and about similarities between acting and science…

Do you prepare any differently for playing real-life characters such as Francis Crick?

It depends who it is and it depends how well known they are. The great thing about stage, which I think differs perhaps a little bit from TV or film, is that the need for an impression is not necessarily as great. For me, it has to be relevant to the story that you’re doing. You don’t want to necessarily go out and do an impression or take it too literally, trying to become that person, if it doesn’t suit the narrative that you’re in

The profession of science and the profession of theatre are to an extent are very very similar

The great thing about Crick is that there’s plenty of footage of him. But he’s not known for his personality so much within the public consciousness in a wider sense, than he is for what he did and what he represents. I’ve been able to pick and choose and have quite a lot of artistic license with how I’ve portrayed him. I think the same is true of everyone else [in the play]. I think the most important thing is that you’re honest and truthful rather than trying to do an all singing, all dancing impression of someone.

Watson famously opens his account in The Double Helix by saying ‘I have never seen Francis Crick in a modest mood’. Is that something you try to get across?

I think within our story Watson is the more demonstrative. I think perhaps in history Crick was the more demonstrative, running into The Eagle and standing on the table and saying he’d discovered the secret of life. But I think in the ‘race’ for DNA, as it’s depicted in this play, Crick is depicted a little bit more as wanting to do the right thing. And certainly reading the letters between Watson and Crick and with Wilkins running up to and after the publication of double helix, you see how Crick is very keen not to overemphasise the ‘Watson and Crick’ element of it. He wants to concentrate on the science rather than the personality of the discovery. That’s quite nice to play, and it gives a nice dynamic between Watson and Crick in the play.

The shame of it is that it became a race when it didn’t really need to be

Crick sounds like quite a guy. I think especially at that age and that time they enjoyed the stardom of it. I think all human beings have an ego and within science – the nature of this discovery and how it came about – and what I’ve learned about it – these were two men with egos to match the discovery. Their relationship, along with Wilkins, and obviously with Rosalind Franklin, is really interesting.

How do you think the play deals with that fact that Rosalind Franklin is not a household name like Watson or Crick?

Part of what’s been happening quite a lot since the discovery really is to redress the balance of exactly how important each scientist was. I think what really is the truth of it is they were all equally important. They all added something to it. It was just the fact that they weren’t working together as a whole team. If they had been working together and everyone had been sharing all of the information all the time, the person who came to the discovery may well have been Rosalind Franklin, it may have been Maurice Wilkins, it may still have been Watson or Crick or both. But because Wilkins and Franklin were working separately to Watson and Crick, the shame of it is that it became a race when it didn’t really need to be. Or if it was a race, it was a race with Linus Pauling at Caltech.

I think what really is the truth of it is they were all equally important

There’s a shame that success and the search for success gets in the way of what it is they’re actually trying to find for the sake of something bigger and better than that. I think that’s what the play brings out beautifully and it examines the cost to every person within the story including Gosling and Caspar as well. For a play that deals with the science so well – takes an audience through the science so clearly- to be able to bring that into it as well is a real triumph and I think Anna Zeigler has done it brilliantly.

You visited the site of the labs at Kings College London where Franklin and Wilkins worked. Did you find that helpful?

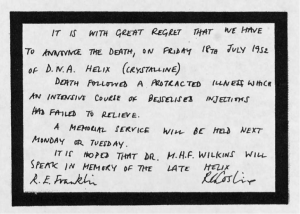

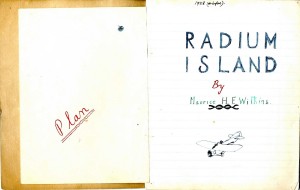

They put out a wonderful exhibition for us, which anyone can go and see if you give them some notice. We saw Photograph 51, we saw Wilkins’ story called Radium Island which he wrote when he was twelve – which was amazing. We saw lots of letters and postcards between all of them. We saw Rosalind Franklin’s epitaph for the DNA helix – a brilliant thing where she writes what is almost like a gravestone for the very thing she was trying to discover.

It was absolutely fascinating to find the correlations, not just within history and this time, but also the correlations between success (and what success is) and the nature of personality within the profession of science and the profession of theatre. They are to an extent are very very similar.

Professor Brian Sutton was speaking to us about the things that he’s working on. There are fine lines between getting something right, winning the Nobel, or getting lots of funding or getting an institute named after you and getting it wrong and going out into the wilderness forever. It was absolutely brilliant and I think without that we would have been a little bit at sea, so it was critical really.

We’re on such fine lines taking an audience through a human story, a historical story and a scientific story

What role did writer Anna Zeigler play in the rehearsal process?

She was there for a week at the beginning of the rehearsal period, which was great because it’s a relatively new play, certainly new here [in the UK]. So there might be things that need to change, lines that need to change, Americanisms that don’t quite fit with the English vernacular. She was very very flexible, there were lines added, lines taken away, things changed, which was great to have. She was very flexible and not overly protective of her work and obviously trusts [director] Michael Grandage and Michael Grandage trusts her as well so it was a lovely thing to have. There’s been lots of involvement by her and it’s just lovely to see a young writer enjoying herself, having a show on in the West End. It’s amazing for her. It just makes it for us another reason to make sure we get it right.

There’s relatively little stage direction in the text of the play. Does that allow flexibility as an actor?

Kind of the opposite. There’s flexibility, obviously, and there should always be in order to be able to play around in rehearsal and try things out. But when it comes to it, the kind of concept that we have with the play, it’s incredibly delicate and technically very very acute so there isn’t a lot of ‘there’s your lighting space go out and play with it’. We’re on such fine lines taking an audience through a human story, a historical story and a scientific story. So we’ve got lots of different things going on that we need to take an audience through in ninety minutes. Only ninety minutes to be able to create the right kind of dramatic atmosphere and to serve the play properly.

In the last RSC season you were starring in Love’s Labour’s Lost and Love’s Labour’s Won while Tom Morton-Smith’s Oppenhiemer was playing concurrently in the adjacent Swan Theatre. Do you think there’s a growing appetite with audiences for theatre with scientific themes or scientific biography?

I’d like to say yes but also if I’m honest there happens to be two plays within a year of each other that were just bloody well written, that happen to be about scientific things. I think if two plays came out that were about bakery (which I’m sure after Bake Off there will be!) and if they’re as well written I think that they could possibly go into town if you get the right companies, the right actors, directors and obviously producers who want to do it in the West End.

I wouldn’t like to say it’s a coincidence because I think there is a taste for it. Great productions need an audience that wants to go and see these plays, these stories. And they do and they did with Oppenheimer and it was brilliant, and I think ours is as well. I think it’s a happy coincidence if it is one but I’d like to think it isn’t. I certainly would go and see Oppenheimer if I wasn’t next door in the other theatre and could just pop in and see it. I think everyone that I’ve heard that saw it loved it. I hope that more [such plays] come out in the future, that would be great.

Photograph 51 is currently playing at the Noël Coward Theatre, booking until 21st November

Q&A with Director Michael Longhurst

Michael Longhurst has directed many critically acclaimed productions, including Nick Payne’s Constellations in the West End and Broadway. Longhurst is an Associate Director at Southampton’s Nuffield Theatre and his new version of Caryl Churchill’s A Number for Nuffield recently transferred to London’s Young Vic Theatre. Science Centre Stage spoke to Michael Longhurst about his views on science in theatre and on how he worked with designer Tom Scutt on the remarkable stage set for A Number.

A Number was first produced in 2002 at a time when cloning was very much in the public conscience (not least because of ‘Dolly the Sheep’). What stimulated you to direct A Number again now?

It’s a play that I had read at drama school and had fallen in love with at that moment. I think the line-by-line writing that Carol makes the scenes out of is extraordinary. I studied philosophy at university and I think the thematic ideas of the play are really interesting. They go beyond and above the idea of cloning and into the idea of personal identity, and beyond and above the idea of nature and nurture and into the idea of freewill and determinism. She is so erudite in packing in so many ideas into a very short, punchy play and it’s an incredibly exciting theatrical premise.

Science is a key enabler in understanding who we are, who we are now and who we are becoming.

Fundamentally, we watch an actor pretend to be more than one version of himself, which is absolutely the most basic part of acting and theatre. It allows us to access the idea of a clone with the same genetics but who behaves differently. I love the simplicity, theatricality and complexity of the ideas it draws on. We were looking for an exciting project for Southampton University (where The Nuffield is based). It has a lot of specialization in biomedicine, so we hoped that it would appeal to some of the audience there. I was working with designer Tom Scutt, who also designed Constellations, and we were excited about the design opportunity to really push a conceptual version of this play in how we staged it. The strength of reaction is one of the major factors that has brought it to life again and brought it into town (at the Young Vic).

In rehearsals we were looking at the progress of the genetic world and interestingly as science advances there’s nothing that makes the play obsolete. The ideas that Caryl Churchill puts forward in the play are still pressing and they become more pertinent the more familiar we become with genetic advances and possibilities. Crudely, we haven’t yet cloned a human so the play’s not yet out of date. It is still a play that is asking- ‘what if ?’ The fact that we are more aware of the advances, such as being able to edit the human genome means that out idea of it as something that is in the dim and distant future in some dystopian world is being eroded. Our world is getting closer to this and I think that makes the ethical questions of the play present more pressing.

In developing the production did you talk to scientists in the similar manner to the way that you and Nick Payne did with Constellations?

Interestingly, the play never mentions the word cloning. The characters, certainly the clones, aren’t aware of this process. So in some sense it wasn’t something that the characters in the play necessarily understood. It was an opportunity that was offered to the father and that he benefits from and it’s a complete shock and surprise to the son. We did work in rehearsals to try to understand how cloning works, but actually we didn’t go out to meet scientists who are experts in their field because the characters themselves have a lay understanding of cloning, which we supplemented by research in the rehearsals.

How do you go about the process of putting together ideas with stage designer Tom Scutt?

Whenever I enter a design process it feels like there’s what I call top-down and bottom-up work. Top down work asks what are the themes that we are trying to capture? How can we use metaphor? How can we create an environment that has an emotional resonance with what we’re trying to say about the play? And then there’s the practical stuff- the bottom-up stuff – which is what does the play need? A Number actually needs nothing. With two bodies and no props, it frees you from many stage constraints. We decided at Nuffield that we wanted to give the audience a new experience, so we created an installation. We weren’t doing a traditional proscenium arch production of it. We were allowed to play with capacity, and make it an incredibly intimate experience. Tom hit on the idea of using mirrors, which felt like he had very cleanly, profoundly and simply hit upon both the ideas of identity – who are we? – and the idea of a multiplicity of reflections. Often as a director your job is to have these thematic discussions with a designer, and then be brave when they offer you an exciting solution. In a piece of live theatre the actors and audience are sharing a space, and in this instance I put them behind a glass wall and used microphones. But I hope that in addition to the ideas of reflection and identity, it also gives the audience a feeling of watching an interrogation. It’s not dissimilar to when you go to a police line-up through a two-way mirror. I think what that does is tie into the ethical issues, the idea of responsibility, the idea of our agency, the idea of guilt, blame and consequence. I think that all of those were useful social ideas to bring up in a stage design.

Often as a director your job is to have these thematic discussions with a designer, and then be brave when they offer you an exciting solution.

Do you think there is complementarity with Jennifer Haley’s play ‘The Nether’ which literally depicts an interrogation in a near-future science fiction scenario?

Yes, absolutely. Both are taking out technological capabilities and pushing them a little bit further, looking at how humanity will respond if we are able to do those things. And do we like how humanity could respond? And therefore do we want our society to go in that direction? I think that’s the value of all “sci-fi work” is that it allows you to examine the society that we are in through looking at a society we’re not in.

There are productions of A Number that have used test tubes a lot and very heavy scientific aesthetic and I think potentially that might have been interesting when the play first came out – when there was a sort of hype and horror around cloning. Actually what we wanted to do was push our aesthetic into a slightly different place. I put the idea of an interrogation room, which is more about responsibility and ‘blame’.

Did recent public debate and legislative changes surrounding mitochondrial donation influence this new production of A Number?

These advances are having huge gestalt shifts in our thinking, the idea of a three parent family, or the idea of being able to edit our genes are huge. The fact that we can’t achieve it at a certain level doesn’t mean conceptually we’re not on a certain pathway. It seems like as soon as we acknowledge the possibility of editing the genome, then we’re able to correct genetic diseases but we’re also a step nearer to eugenics. That is an important thing that we need to be thinking about.

Do you think the success of plays such as Constellations and A Number indicates a growing place for science in the cultural life?

I have directed predominantly new writing. I love theatre that is exploring who we are and science is a key enabler in understanding who we are, who we are now and who we are becoming. I think a writer who uses science to explore and answer that question can often tap into hugely exciting, revelatory and challenging areas of our humanity. I think as a theatre maker when you have a play that is exploring science, often formally – as is in the case of Constellations and actually in the case of A Number, both of those plays have the form of the play, or at least the theatrical experience dictated by the science. In A Number you’ve got one actor playing several clones. He literally embodies the act of cloning – but it also makes very good theatre. And in Constellations the form of the play was repeated versions of the multiverse. It’s an exciting theatrical provocation for an audience. In the design there’s lots of potential for metaphor. All of these things appeal to me as I’m interested in analytical ways of thinking. I guess it’s a personal preference but I think it’s a really valuable branch of theatre.

Would you argue that science in theatre works best when the science informs the structure rather than the didactic content?

Absolutely. If we’re trying to understand scientific principles there are probably much deeper lectures that one could go to, essays or journals that one could read or documentaries that one could watch. But I think what theatre can do is dramatize emotional consequences of what the science is. It can help us have an emotional understanding and ask the ethical question. Constellations poses what does it feel like to be in a multiverse? Actually, what that does is it makes you realize that I can’t access these other parallel universes, so my choices in this one are all the more precious. And that is the emotional feeling of the play.

I think A Number asks if we could do these things then what would be the ramifications be? What does it mean – this idea that man is born equally? Well genetically he’s not. If we are given these opportunities, how can they be used or abused?

A Number, directed by Michael Longhurst, runs at London’s Young Vic until 15th August.

The Royal Court Theatre tour of Constellations is at Trafalgar Studios until 1st August.

A Dramatic Experiment: Science on Stage – Video of Panel Discussion

A recording of the panel discussion on science and theatre held at the Royal Society on Monday 11th May in partnership with the Royal Shakespeare Company is now available online via the Royal Society website.

Chaired by Erica Whyman

With Kirsten Shepherd-Barr, Tom Morton-Smith, Marcus du Sautoy and John Barrow.