Fresh from an acclaimed season with the Royal Shakespeare Company, Edward Bennett is currently in the West End playing Francis Crick in Photograph 51 alongside Nicole Kidman. Edward told Science Centre Stage about his impressions of Crick, about visiting the historic labs at Kings College London and about similarities between acting and science…

Do you prepare any differently for playing real-life characters such as Francis Crick?

It depends who it is and it depends how well known they are. The great thing about stage, which I think differs perhaps a little bit from TV or film, is that the need for an impression is not necessarily as great. For me, it has to be relevant to the story that you’re doing. You don’t want to necessarily go out and do an impression or take it too literally, trying to become that person, if it doesn’t suit the narrative that you’re in

The profession of science and the profession of theatre are to an extent are very very similar

The great thing about Crick is that there’s plenty of footage of him. But he’s not known for his personality so much within the public consciousness in a wider sense, than he is for what he did and what he represents. I’ve been able to pick and choose and have quite a lot of artistic license with how I’ve portrayed him. I think the same is true of everyone else [in the play]. I think the most important thing is that you’re honest and truthful rather than trying to do an all singing, all dancing impression of someone.

Watson famously opens his account in The Double Helix by saying ‘I have never seen Francis Crick in a modest mood’. Is that something you try to get across?

I think within our story Watson is the more demonstrative. I think perhaps in history Crick was the more demonstrative, running into The Eagle and standing on the table and saying he’d discovered the secret of life. But I think in the ‘race’ for DNA, as it’s depicted in this play, Crick is depicted a little bit more as wanting to do the right thing. And certainly reading the letters between Watson and Crick and with Wilkins running up to and after the publication of double helix, you see how Crick is very keen not to overemphasise the ‘Watson and Crick’ element of it. He wants to concentrate on the science rather than the personality of the discovery. That’s quite nice to play, and it gives a nice dynamic between Watson and Crick in the play.

The shame of it is that it became a race when it didn’t really need to be

Crick sounds like quite a guy. I think especially at that age and that time they enjoyed the stardom of it. I think all human beings have an ego and within science – the nature of this discovery and how it came about – and what I’ve learned about it – these were two men with egos to match the discovery. Their relationship, along with Wilkins, and obviously with Rosalind Franklin, is really interesting.

How do you think the play deals with that fact that Rosalind Franklin is not a household name like Watson or Crick?

Part of what’s been happening quite a lot since the discovery really is to redress the balance of exactly how important each scientist was. I think what really is the truth of it is they were all equally important. They all added something to it. It was just the fact that they weren’t working together as a whole team. If they had been working together and everyone had been sharing all of the information all the time, the person who came to the discovery may well have been Rosalind Franklin, it may have been Maurice Wilkins, it may still have been Watson or Crick or both. But because Wilkins and Franklin were working separately to Watson and Crick, the shame of it is that it became a race when it didn’t really need to be. Or if it was a race, it was a race with Linus Pauling at Caltech.

I think what really is the truth of it is they were all equally important

There’s a shame that success and the search for success gets in the way of what it is they’re actually trying to find for the sake of something bigger and better than that. I think that’s what the play brings out beautifully and it examines the cost to every person within the story including Gosling and Caspar as well. For a play that deals with the science so well – takes an audience through the science so clearly- to be able to bring that into it as well is a real triumph and I think Anna Zeigler has done it brilliantly.

You visited the site of the labs at Kings College London where Franklin and Wilkins worked. Did you find that helpful?

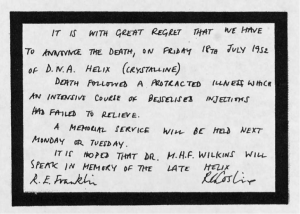

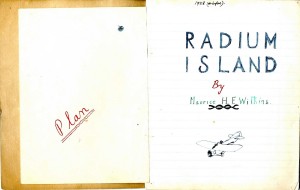

They put out a wonderful exhibition for us, which anyone can go and see if you give them some notice. We saw Photograph 51, we saw Wilkins’ story called Radium Island which he wrote when he was twelve – which was amazing. We saw lots of letters and postcards between all of them. We saw Rosalind Franklin’s epitaph for the DNA helix – a brilliant thing where she writes what is almost like a gravestone for the very thing she was trying to discover.

It was absolutely fascinating to find the correlations, not just within history and this time, but also the correlations between success (and what success is) and the nature of personality within the profession of science and the profession of theatre. They are to an extent are very very similar.

Professor Brian Sutton was speaking to us about the things that he’s working on. There are fine lines between getting something right, winning the Nobel, or getting lots of funding or getting an institute named after you and getting it wrong and going out into the wilderness forever. It was absolutely brilliant and I think without that we would have been a little bit at sea, so it was critical really.

We’re on such fine lines taking an audience through a human story, a historical story and a scientific story

What role did writer Anna Zeigler play in the rehearsal process?

She was there for a week at the beginning of the rehearsal period, which was great because it’s a relatively new play, certainly new here [in the UK]. So there might be things that need to change, lines that need to change, Americanisms that don’t quite fit with the English vernacular. She was very very flexible, there were lines added, lines taken away, things changed, which was great to have. She was very flexible and not overly protective of her work and obviously trusts [director] Michael Grandage and Michael Grandage trusts her as well so it was a lovely thing to have. There’s been lots of involvement by her and it’s just lovely to see a young writer enjoying herself, having a show on in the West End. It’s amazing for her. It just makes it for us another reason to make sure we get it right.

There’s relatively little stage direction in the text of the play. Does that allow flexibility as an actor?

Kind of the opposite. There’s flexibility, obviously, and there should always be in order to be able to play around in rehearsal and try things out. But when it comes to it, the kind of concept that we have with the play, it’s incredibly delicate and technically very very acute so there isn’t a lot of ‘there’s your lighting space go out and play with it’. We’re on such fine lines taking an audience through a human story, a historical story and a scientific story. So we’ve got lots of different things going on that we need to take an audience through in ninety minutes. Only ninety minutes to be able to create the right kind of dramatic atmosphere and to serve the play properly.

In the last RSC season you were starring in Love’s Labour’s Lost and Love’s Labour’s Won while Tom Morton-Smith’s Oppenhiemer was playing concurrently in the adjacent Swan Theatre. Do you think there’s a growing appetite with audiences for theatre with scientific themes or scientific biography?

I’d like to say yes but also if I’m honest there happens to be two plays within a year of each other that were just bloody well written, that happen to be about scientific things. I think if two plays came out that were about bakery (which I’m sure after Bake Off there will be!) and if they’re as well written I think that they could possibly go into town if you get the right companies, the right actors, directors and obviously producers who want to do it in the West End.

I wouldn’t like to say it’s a coincidence because I think there is a taste for it. Great productions need an audience that wants to go and see these plays, these stories. And they do and they did with Oppenheimer and it was brilliant, and I think ours is as well. I think it’s a happy coincidence if it is one but I’d like to think it isn’t. I certainly would go and see Oppenheimer if I wasn’t next door in the other theatre and could just pop in and see it. I think everyone that I’ve heard that saw it loved it. I hope that more [such plays] come out in the future, that would be great.

Photograph 51 is currently playing at the Noël Coward Theatre, booking until 21st November